Why City Hall will be Hong Kong’s youngest structure declared as a monument

The 60-year-old City Hall in Hong Kong is set to become its first post-war monument in an unprecedented move by the government that takes into account residents’ shared history and the structure being a beacon for social equality.

Experts said it was rare for authorities and antiquities advisers to prioritise people’s collective memory over historical value when declaring a monument.

The proposal made by the Antiquities and Monuments Office obtained the green light from Antiquities Advisory Board members on Thursday, with two other grade one historical buildings Jamia Mosque in Central and Lui Seng Chun in Mong Kok.

An official declaration will be gazetted by the government in the coming months.

Jamia Mosque will also be declared a monument.

Jamia Mosque will also be declared a monument.

“Around 20 years ago, preservation was often about houses of the upper class or government premises but now times have changed,” said Dr Lee Ho-yin, associate professor of architectural conservation at the University of Hong Kong.

“It is a rare but also a right move to declare City Hall as a monument.”

Ronald Phillips, who designed the complex with fellow Briton Alan Fitch, told the Post on Saturday: “I do believe that the City Hall deserves such a designation.”

Opened in 1962, the site comprises two Bauhaus-style buildings and a memorial garden located on reclaimed land in Central overlooking Victoria Harbour. The hall hosted many historical events in colonial-era Hong Kong, including the inauguration ceremonies of governors and visits of Queen Elizabeth II and other royal family members.

Philips said he was attending a concert by the London Philharmonic Orchestra in London on Sunday, which will almost coincide with the 60th anniversary of the musical group’s performance for the City Hall’s inaugural concert in March 1962.

As part of the multipurpose cultural complex, the low block houses a concert hall, theatre and exhibition gallery, while the higher one contains a marriage registry, public library and recital hall.

The place is also a world-class performance venue, home to one of the city’s flagship orchestras, the Hong Kong Sinfonietta, which performs year-round with more than 100 concerts a season.

An old picture of City Hall from 1962.

An old picture of City Hall from 1962.

“We are not just passing by or going in and out the hall. Most of our generations grew up here and have developed a living circle,” said Raymond Fung Wing-kay, a former government senior architect who took part in the renovation of the complex in 1992.

“I used to study in the library and went to concerts when I was younger, and this is also the place I got married to my wife,” said Fung, 70, who is also a former architectural professor at Chinese University.

While the first city hall, which was demolished between the 1930s and 1940s, was mainly for upper-class social events, the post-war version has become a gathering place for all residents regardless of social status or ethnicity. Anyone can gain access to the library or museum exhibitions and enjoy performances that are free or at affordable prices.

The board on Thursday agreed to declare the complex, which is already a grade one historic building, as a monument for permanent protection.

According to a heritage appraisal report submitted by the government to the board, City Hall marked a change in social equality in the second half of the 20th century in Hong Kong, and has carried residents’ collective memories.

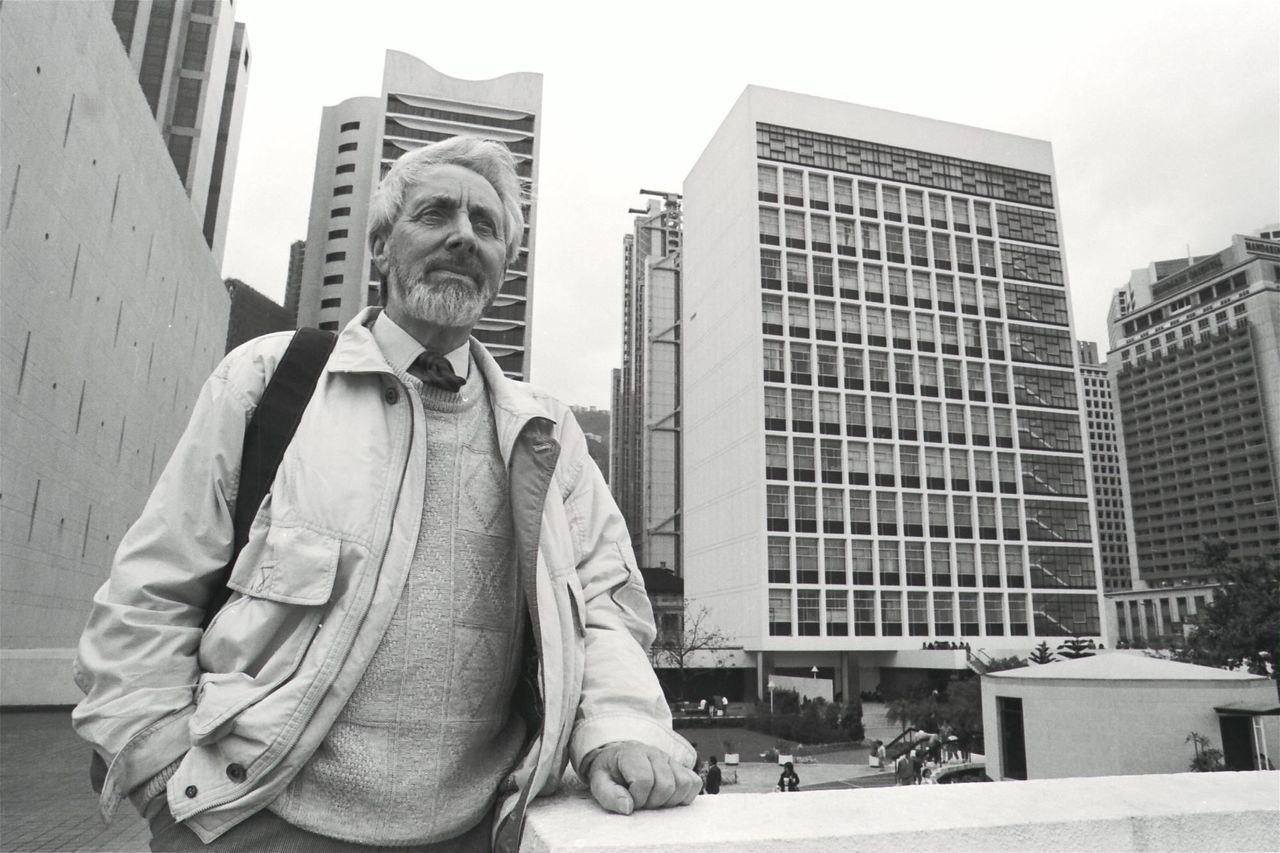

Ronald Phillips, who designed City Hall with fellow Briton Alan Fitch.

Ronald Phillips, who designed City Hall with fellow Briton Alan Fitch.

“As an architect, my period of 13 years in Hong Kong, in particular [my work] on the City Hall, was probably the most fulfilled and happy experience of my professional [life] … We had a wonderful life,” Phillips, who turns 95 this year, told the Post back in 2012.

He added that he was given the utmost freedom when designing the HK$20 million project, unimpeded by bureaucracy. “We were very fortunate. The City Hall started off as a culture centre. It was not for the privileged, but for everyone,” he said.

Philips said he and Fitch had developed a concept for the project that capitalised on the site’s vantage point of Victoria Harbour.

“The outside public area, the memorial garden and piazza in front of the building, were to be a natural extension of the building at ground level to promote freedom of movement and a sense of unlimited space; a public facility which was in very short supply in the city centre, even in the 1950s,” Philips told the Post.

“At the same time, it was essential to keep the hustle and bustle of the city at bay whilst maximising the amount of public access. This building was to be for everyone,” he said.

Fung also said the complex renovation in 1992 took into account the public’s emotional attachment to the structure.

He said back then newlyweds and their guests crowded the Marriage Registry for photos and his team had rebuilt the area by adding a wide staircase from the registry to the memorial garden, now a popular spot for such pictures.

The area surrounding the Memorial Shrine in the garden was also converted into a sunken square, and a water channel was added at the back of the shrine.

“We wanted to make it a more honorary place since the shrine was built to remember the soldiers and citizens who sacrificed themselves in the second world war,” Fung recalled.

Lee said the declaration showed that the city’s heritage preservation was no longer merely limited to building age, pointing to a “global trend”.

There are currently 129 declared monuments in Hong Kong that enjoy legal protection from demolition. Lee added most of them were around for more than 100 years old, with the youngest dating back to the 1930s. All of them are buildings and structures built before the first world war.

Those of merit but of lower heritage values are assigned a grade under a three-tier system, with this rating still modifiable, and the structures open to demolition if they are in the hands or private owners.

City Hall was once at the centre of a public uproar when the government decided to demolish the grade-one Queen’s Pier to pave the way for reclamation. Architects had revealed that the complex had been designed as part of a cluster of historic buildings and structures that form the city’s hub, with the pier in front of City Hall.

“[City Hall] is not completely isolated … but it does not hold the hub as before. And with the reclamation that is now being put in front … [it] has completely destroyed the piazza,” said Phillips, who called the demolition of Queen’s Pier a shame.

The complex – together with the previous Star Ferry pier and its famous clock tower, which were knocked down in 2006 – as well as a dais and the Star Ferry car park, formed Edinburgh Place. Two years later, Queen’s Pier was also demolished.

Phillips said in the earlier interview that the City Hall complex was “beautifully located in front of the Queen’s Pier, which has a history of its own,” and he barely recognised it after the demolition compared with its original form when he began work on it in 1956.

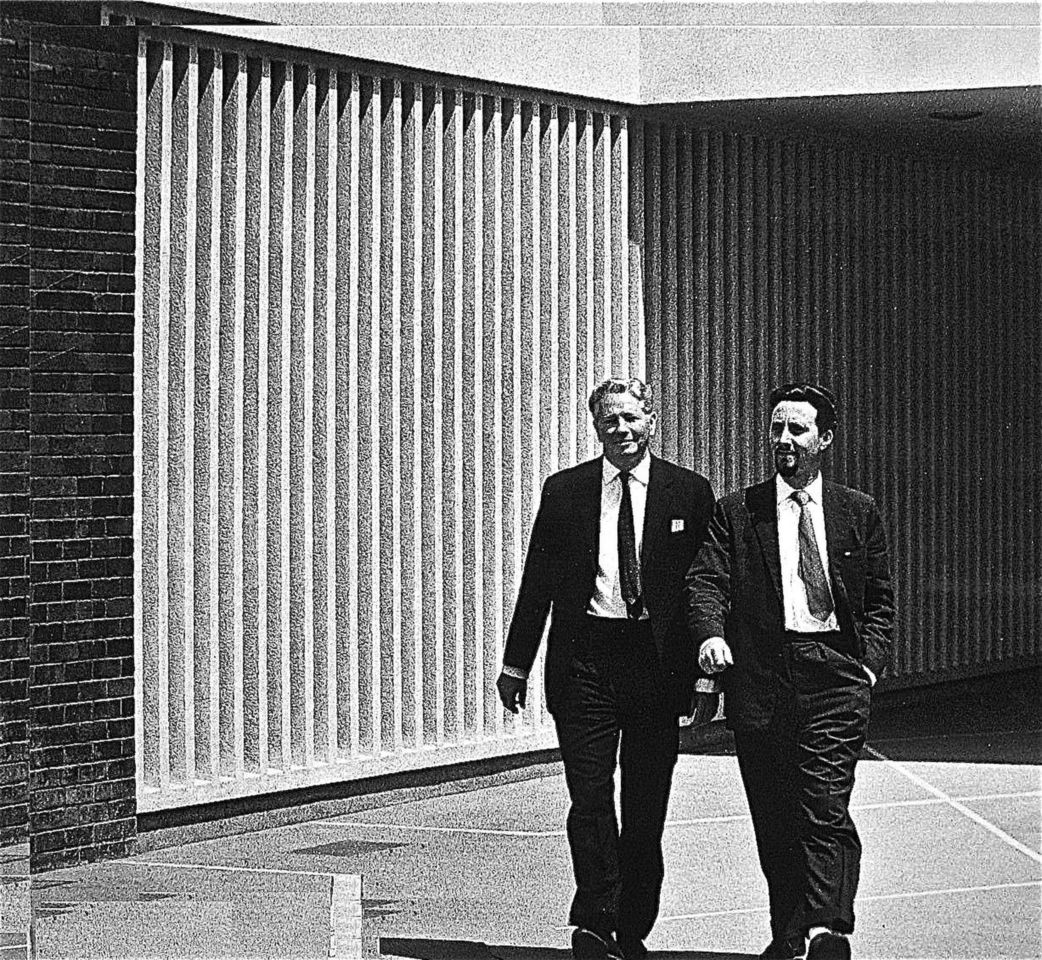

City Hall architects Alan Fitch (left) and Ronald Philips.

City Hall architects Alan Fitch (left) and Ronald Philips.

Other iconic buildings erected after 1950 in the city are also slated to meet the wrecking ball for redevelopment such as the General Post Office, the headquarters of the Garden Company bakery, and the Excelsior hotel.

Countries such as Japan, Britain and the United States have all introduced programmes to identify and conserve modern architecture. Hong Kong Antiquities Advisory Board chairman Douglas So Cheung-tak said in 2019 that more post-war buildings would be assessed in response to public views and global trends.

Board member Wilson Shum Ho-kit also said the antiquities body would take into account more such buildings in the future.

“Like City Hall, we focused on its social value and the influential design style which has been an iconic example of modernist architecture in the city,” Shum said. “We will start looking at more buildings built in the 1950s and 1960s.”

In 2018, the city set aside HK$20 billion for the development of cultural facilities, including an expansion of City Hall. Sources familiar with the policy told the Post that the relevant expansion would be related to the car park area, and the complex would not be affected.