Who is on the move in Boris Johnson’s cabinet reshuffle?

A reshuffle of Boris Johnson’s cabinet is under way. Here’s what we know so far of who is in and out of key positions.

Dominic Raab

Moves from: foreign secretary

To: deputy prime minister, lord chancellor and justice secretary

A true Brexit believer, Raab was closely involved in the Vote Leave campaign. He ran for the leadership in 2019, but ultimately threw his weight behind Johnson, and has been viewed as loyal and trustworthy by No 10 ever since.

When the prime minister was hospitalised with Covid last year, Raab deputised for him, and acted as a key member of the “quad” – with Michael Gove, Rishi Sunak and Matt Hancock – who made critical decisions about the day-to-day running of government.

At one dramatic press conference, Raab revealed the seriousness of the situation by saying he was sure the prime minister would “pull through”.

However, despite being a safe pair of hands during the pandemic, Raab is widely viewed at Westminster to have botched the Foreign Office’s role in the Kabul airlift, not least by continuing with a family holiday in Crete as the Taliban advanced.

He has said the crisis resulted from long-term failures of intelligence and strategy, but the row sparked an outpouring of leaks from within the Foreign Office about his allegedly domineering management style.

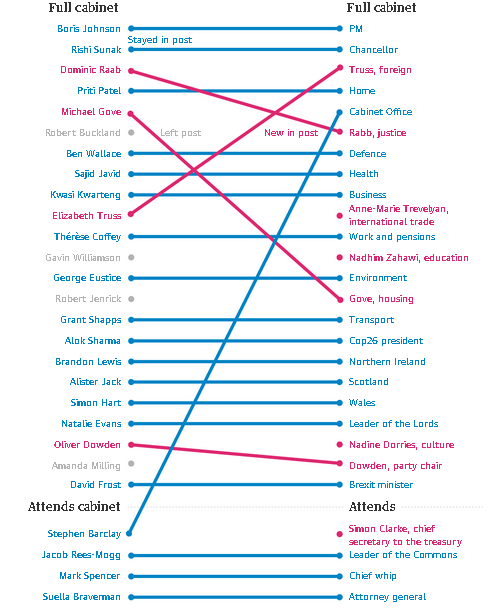

Boris Johnson's new cabinet

Liz Truss

Moves from: international trade secretary

To: foreign secretary

No one in the cabinet’s star has risen quite so dramatically or unexpectedly as Liz Truss’s during Johnson’s tenure in No 10.

Once often tipped as a candidate for the chop during reshuffles, she is now the darling of the Tory members, by far the most popular cabinet minister among Conservatives polled, who love her for her relentless optimism.

She has been lucky in her brief in that regard – as international trade secretary, she had the opportunity to announce plenty of good news about new trade partnerships – even if they might look a little less shiny under scrutiny.

Some in the party had predicted Johnson would not promote a cabinet minister who could rival him in terms of popularity with Tory members, but she has been fiercely loyal to the prime minister and was one of his earliest leadership backers.

Oliver Dowden

Moves from: culture secretary

To: minister without portfolio in the Cabinet Office

One of three then rising stars who gave crucial backing from the moderate wing of the party to Johnson during his leadership bid, Oliver Dowden was rewarded with a cabinet post in the so-called “ministry of fun” only five years after becoming an MP.

He has received relatively little flack in his 18 months at the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport, though he did face calls from China hawks within the Conservative party to clamp down faster on the use of Huawei technology in 5G networks.

Viewed by Downing Street as a safe pair of hands loyal to the government and trusted to go out and bat on a difficult morning broadcast round, Dowden was a former chief of staff to David Cameron. His other government jobs were all in the Cabinet Office.

Nadine Dorries

Moves to: culture secretary

Nadine Dorries’ promotion to the cabinet cements a rapid if very delayed rise to prominence: she got her first ministerial job, a junior health role, in 2020, 15 years after she became an MP.

As a backbencher, Dorries was primarily known for her robust views on areas including abortion and equal marriage, her dislike of Cameron, and media appearances including a brief 2012 stint on ITV’s I’m a Celebrity … Get Me Out of Here!, after which she lost the Tory whip for some months because she had not cleared her absence.

She is a strong supporter of Johnson, which in part explained her move into the ministerial world from May 2020. Dorries is also a successful author, having written a series of mainly historical novels, some drawing on her own background as a trainee nurse in Liverpool. In the last register of MPs’ interests, Dorries listed payments of more than £120,000 over the previous year in royalties and contract payments.

Nadhim Zahawi

Moves from: minister for Covid-19 vaccine deployment

To: education secretary

Nadhim Zahawi has spent some time earning a reputation as a safe ministerial pair of hands, but his promotion to education secretary seems direct reward for his most recent job: minister for vaccines.

The MP for the ultra-safe Conservative seat of Stratford-upon-Avon since 2010, Zahawi was made a junior education minister in 2018, moving to the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy 18 months later. But in late 2020 he acquired a second role, becoming responsible for the Covid vaccine programme under the Department of Health.

Zahawi was credited with the success of the initial programme of jabs, which for a period brought Johnson a notable boost in the polls. A regular choice to go on radio and TV, where he has the ability to sound sensible while saying very little, Zahawi is notably loyal – last week he defended the now-abandoned policy of vaccine passports in the Commons, despite clearly disagreeing with them.

Born in Baghdad to Kurdish parents who fled Iraq for the UK when he was nine, Zahawi is one of the Commons’ richest MPs, as a co-founder of the pollsters YouGov, with interests in other areas such as petroleum before he became a minister.

Michael Gove

Moves from: Cabinet Office minister and chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster

To: housing secretary

If Michael Gove was anxious about a reshuffle, he certainly didn’t not show it on the dancefloor in Aberdeen where he was recently snapped dancing on a solo night out. Gove and Johnson have a history of turmoil, after the former declared his friend unfit to be prime minister in 2016 and launched his own leadership challenge.

Though some senior figures in the party believe Johnson still does not trust Gove, their relationship has healed during the Covid crisis. Gove has had a wide brief in the Cabinet Office, managing the implementation of lockdowns and new systems for restrictions as well as managing Brexit negotiations before that was taken over formally by David Frost since his elevation to the cabinet.

Though his role at the Cabinet Office has put him at the heart of the most challenging and sensitive decisions in government, he is said by friends to want the challenge of a new department.

Steve Barclay

Moves from: chief secretary to the Treasury

To: Cabinet Office minister and chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster

Steve Barclay was one of Johnson’s key leadership backers and was given a meaty job in the Treasury after his job as Brexit secretary became in effect redundant. In that role, Johnson had put him in charge of domestic preparations and handed the negotiations to David Frost.

Johnson made a big show of removing the role from Barclay at 11pm on 31 January 2020 and closing down his department, to signal that he had “got Brexit done”. Barclay did not have to wait long for a return to government: he was the quiet beneficiary of Sajid Javid’s abrupt resignation as chancellor after a fallout with Dominic Cummings. Johnson promoted Rishi Sunak and Barclay took his job as chief secretary. In the role, he has helped steer through the national insurance rise, a thankless task that has won him some brownie points.

Simon Clarke

Moves to: chief secretary to the Treasury

Simon Clarke is MP for Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland. He will attend cabinet meetings in his new role.

Boris Johnson’s reshuffle – the winners and losers

Source: Institute for Government. At 8.45pm, 15 September

Source: Institute for Government. At 8.45pm, 15 September

Out: Gavin Williamson

Gavin Williamson’s demotion from education secretary was so well heralded that the main surprise of Tuesday’s news is that it took so long.

In the job since 2019, Williamson has in effect served as a political shield for Johnson over Covid-related failures in schools and university, most notably the fiasco over A-levels in 2020 when Williamson and his department ignored months of warnings about issues with an algorithm to award grades in the absence of exams, only to change tack amid outrage at the perceived unfairness of the results.

Since then, predictions of his demotion or removal had come almost weekly, and it was assumed by many he was largely kept in post to usher through another set of disrupted summer exams.

The MP for South Staffordshire since 2010, Williamson has managed to combine a series of high-profile roles and high-level political patronage with a somewhat blundering public image, cemented by his confident assertion in an interview last week that he had met the footballer Marcus Rashford, only for it to emerge that it had been another black sportsperson, the rugby player Maro Itoje.

Williamson’s ascent began under Theresa May, who made him chief whip in 2016. He embraced the dark arts elements of the role with gusto, very publicly keeping a live tarantula on his desk. He was seen as a highly effective chief whip, someone who understood the political manoeuvrings over the Tory party, and was promoted by May in 2017 to become defence secretary.

This role seemed less of a good fit for Williamson – he was widely mocked for saying Russia should “go away and shut up” – and it came to a sudden and crashing end when May sacked him for leaking national security council discussions about Huawei’s involvement in the UK’s 5G network, which he denied.

This would be enough to permanently sink most careers, but Williamson was an integral member of Johnson’s campaign to succeed May as Tory leader, and was rewarded with being made education secretary.

It is fair to say that in the role Williamson had not notably impressed the education sector, even before the exams debacle. Now it – and Williamson – must wait to see what comes next.

Out: Robert Buckland

Robert Buckland has revealed that he has been sacked as justice secretary, tweeting: “I am deeply proud of everything I have achieved. On to the next adventure.” He is widely believed at Westminster to have been moved aside to allow Dominic Raab to take the post.

A former remain campaigner, Buckland always appeared an unlikely member of a Johnson cabinet, but the South Swindon MP had won the respect of the judiciary during his two years in the post.

He recently oversaw a review of the process of judicial review, the findings of which were perhaps more balanced than some in No 10 might have liked to see, and is also believed to have been sceptical about Johnson’s decision to increase national insurance contributions to pay for health and social care.

Out: Robert Jenrick

The communities and housing secretary throughout the Johnson era up to now, Robert Jenrick had previously clung to his post despite controversies that would have sunk many ministers in earlier eras.

The most notable of these came after it emerged Jenrick had sat next to the former newspaper magnate Richard Desmond at a Conservative fundraising event and that Desmond had shown him a PR video for the 44-storey block of flats he was developing in east London.

Two months later, Jenrick overruled the local council and the government’s Planning Inspectorate to approve the £1bn development. He did this the day before a community levy would have come into force, providing £45m for the council, Tower Hamlets, to spend on local infrastructure. The council challenged the decision in court and Jenrick backed down, conceding a potential for bias.

Jenrick, who has represented Newark in Nottinghamshire since winning a byelection in 2014, has faced some criticism for his local ties. The former solicitor owns two properties in London, as well as Eye Manor, a Grade I-listed home in Herefordshire, and local people have complained they do not see him as much as they would like.

Out: Amanda Milling, Conservative party co-chair

One of the least high-profile participants in Wednesday’s reshuffle, Amanda Milling shot into the cabinet from a lowly junior whip role in February 2020, when she was made joint chair of the Conservative party alongside Ben Elliot.

In the role, Milling has been notably less controversial than Elliot, who has faced allegations of lobbying connected to his business role, but she has also been seen as largely underwhelming.

The 46-year-old former market researcher, who keeps a photograph of Margaret Thatcher above her desk, has been the MP for Cannock Chase in Staffordshire since 2015. She backed remain in the Brexit referendum, but then supported Johnson to succeed May as Tory party leader.

It seems likely she will return to the relative obscurity of the backbenches.

Staying in the same post

Priti Patel: home secretary

Sajid Javid: health secretary

Thérèse Coffey: work and pensions secretary

Ben Wallace: defence secretary

George Eustice: environment secretary

Kwasi Kwarteng: business secretary

Grant Shapps: transport secretary

Alok Sharma: Cop26 president

Brandon Lewis: Northern Ireland secretary

Alister Jack: Scotland secretary

Simon Hart: Wales secretary

Mark Spencer: chief whip

David Frost: Cabinet Office minister responsible for Brexit

Natalie Evans: leader of the House of Lords

Kit Malthouse: policing minister (but now attending cabinet)