Sir John Curtice: The man who gets elections right

When Professor Sir John Curtice pronounces on elections, politicians and pundits listen.

Knighted in 2017, he is perhaps the only psephologist in the UK who is routinely, albeit reluctantly, recognised in the street.

"I live with it," he says. "I don't live for it."

As 10pm chimes on the final Thursday of a general election, the last voters finish casting their ballots.

It's then that Sir John, who's been working on general elections since the 1970s, interprets the exit poll - in which voters at about 140 selected polling stations fill in second ballots, indicating which candidate they've chosen.

And that's what he uses to tell the world who is likely to become the next prime minister.

"I don't worry about what happens at the close of voting," he says. "The more nervous period is later on in the night, when we actually see how accurate we've been."

For local elections like this week's in England, Scotland and Wales there are no exit polls - the same applies for the Northern Ireland Assembly elections on the same day.

But Sir John still has to make a call on what the vote means for the next general election.

"Someone wants you to give a reasonably realistic estimate of how the parties would do if voting shares were applied across the country as a whole, and across the four nations," he says.

"We're still trying to get the people an idea of where the story's going. It's quite hard."

The work of Sir John, professor of political science at the University of Strathclyde, and his colleagues starts months before the glamour of election night.

By the time polls open on the day of a general election, hundreds of hours of work finessing methods have gone in, ready for Sir John and his team of five or six experts to analyse exit poll results as they are phoned in.

"We tend to start in the middle of the morning, 11am or 12ish," he says. "No earlier, really, because we have to work until sometimes well into the following day."

The team hand in their mobile phones and sit together in a guarded room in a secret location.

By early afternoon - several hours before the rest of the country - Sir John has a good idea of who is likely to be the next prime minister.

After the usual early-evening surge in voting and exit polls, he and his experts sketch out their broader thoughts on a whiteboard.

"We're beginning to brief the people who really need to know, such as main representatives from TV companies," says Sir John.

"Then we get to the tough end of the business, saying this is what [result] we're going to go for now."

After the exit poll-based prediction is revealed at 10pm there is the wait to see if it is right - or as right as it can be.

Sir John's team leave the sealed room, spending the rest of the night in the TV studio.

This week's elections, lacking exit polls, will not have the amount of prior data that a general election provides.

Brain food? Sir John's team like to eat healthily but a slice of pizza now and then goes down well

Brain food? Sir John's team like to eat healthily but a slice of pizza now and then goes down well

"The story is emerging throughout the night," 68-year-old Sir John says. "For last year's local elections I got four hours' sleep [when there was a lull in results] and I got up at 5am to start again, but that doesn't happen for general elections."

For these, he is awake for at least 36 hours straight as he goes through the results, while writing online stories and appearing on radio and TV.

His team choose food from takeaway menus. "We try to have something healthy," says Sir John, "but we had pizzas last year, I think."

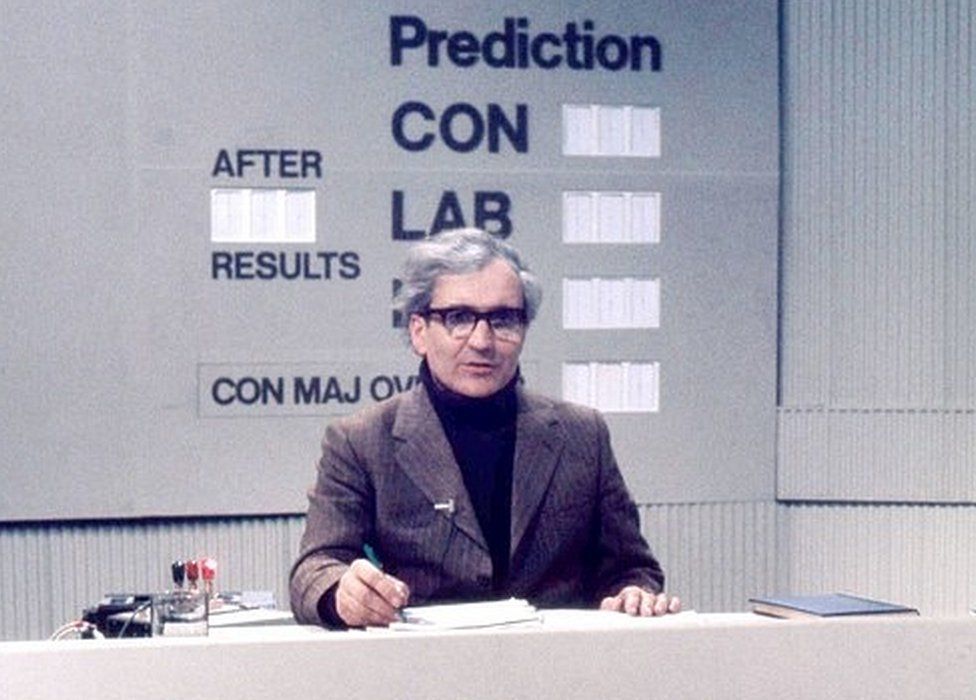

David Butler, the UK pioneering on-screen pollster, was a mentor to Sir John

David Butler, the UK pioneering on-screen pollster, was a mentor to Sir John

"It gets more difficult to do the job the longer you're awake," says Sir John. "Lack of sleep destroys your short-term memory, so you have to get as well prepared as you can.

"Most people are not sitting up all night watching this stuff. But we still have to be ready to explain to people in the morning what's happened."

But Sir John resists the temptation to grab 40 winks.

"The way I see it is that, if you've missed a night of sleep, you've missed a night. You don't want to go back to sleep early and ruin sleep patterns. You have to keep going until nine or 10 the next evening."

By mid-morning on Friday, general election results show whether Sir John was right or wrong.

Broadcasters continue for several more hours to ask him for in-depth analysis on why people voted as they did.

And for local elections, he's called on throughout the day to give his developing state of-the-political-nation thoughts.

After that, it's time - finally - for bed.