Platinum Jubilee: What does Scotland think of the Queen?

Bonfire Night 1985 found the pupils of Kingsmuir Primary School in Angus standing in line on a country road, waiting to pay our respects to the House of Windsor.

The object of our devotion was the Queen's daughter, Princess Anne, who was to pass through a nearby village, presumably on the way from one regal duty to another.

We had made pieces of card with the union flag on one side and letters spelling out the name of our school on the other, which we were to flip around on cue.

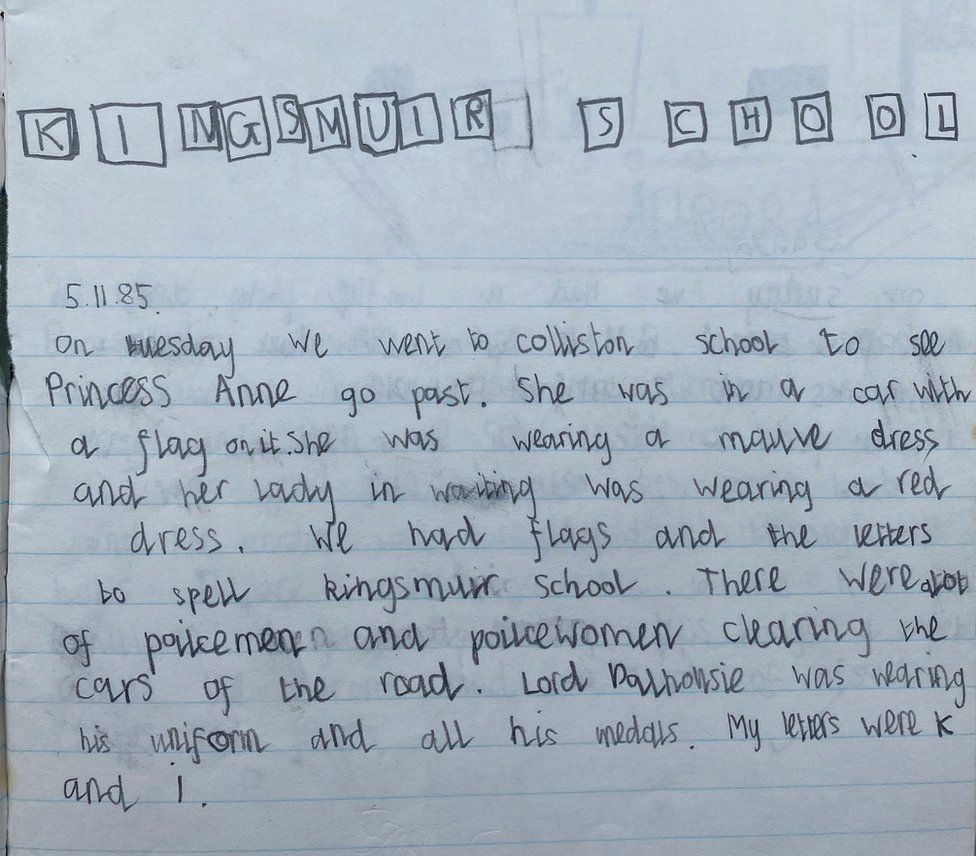

The princess royal swept past us in seconds. Your eagle-eyed eight-year-old correspondent recorded that she was "in a car with a flag on it" and "wearing a mauve dress".

"Lord Dalhousie was wearing his uniform and all his medals," added your cub reporter, the 16th earl having served in North Africa with distinction during the war, earning the Military Cross.

An eight-year-old James Cook recorded the news in his school jotter

An eight-year-old James Cook recorded the news in his school jotter

It is difficult to imagine a repeat of this scene in Scotland now, and not just because the earl is no longer with us and Kingsmuir Primary has long since closed.

The truth is that while there are pockets of enthusiastic partying in Scotland this weekend, the Platinum Jubilee is largely invisible in many parts of the country.

"Scotland is a part of the UK where there is definite, palpable republican sentiment, even now during the Queen's reign," says Anna Whitelock, professor of modern monarchy at City, University of London.

That was also evident a decade ago when I took a spin to sense the mood in what was once known as the Second City of the Empire.

"Have just driven through Glasgow city centre and west end. No union flags or bunting to be seen," was my summary of the Diamond Jubilee.

This should not be a surprise. Opinion polls consistently suggest an underlying lack of enthusiasm for the monarchy in Scotland compared to other parts of the UK.

Last month a Focaldata survey for the British Future think tank indicated that a quarter of people in Britain would favour the nation becoming a republic at the end of the current Queen's reign. In Scotland the figure was well above a third.

The poll also suggested that while 58% of people in Britain as a whole favoured keeping the monarchy, just 45% felt the same in Scotland.

Other polls in recent years have produced similar results.

The monarchy "is definitely less popular in Scotland than it is south of the border," says Sir John Curtice, professor of politics at Strathclyde University.

And yet the Scottish National Party's ambition is to revoke the 1707 Union of the Parliaments but not the 1603 Union of the Crowns, a point First Minister Nicola Sturgeon reiterated in an interview with BBC Scotland political editor Glenn Campbell.

The SNP maintains a royalist position despite the fact that many of the ties that bound Scotland into the union — ties in many ways personified by Elizabeth herself — are fraying, and despite evidence of a link between support for independence and support for an elected head of state.

The Queen opens the sixth session of the Scottish Parliament in October 2021

The Queen opens the sixth session of the Scottish Parliament in October 2021

According to Sir John, polling suggests that between half and two thirds of independence supporters would prefer a republic, while between two thirds and three quarters of independence opponents want to keep the monarchy.

"One of the political difficulties for the monarchy north of the border is that as an institution it is now somewhat caught up in the constitutional debate," says Sir John.

As memories fade of the unifying experience of the war, and the British Empire becomes a topic for critical study rather than a source of wealth, influence and pride for Scotland, the very notion of Britishness is changing.

The British Future report reckons only one in six people in England feels more British than English, and they are more likely to be young, urban, liberal, pro-European and from ethnic and faith minorities.

Scotland, in this sense, really is a foreign country, where feeling more British "has precisely the inverse sociological correlations: being older, more Christian, whiter, more right-leaning and more Eurosceptic", according to British Future.

The past two decades have also seen a shift of emphasis in Scottish public life from London to Edinburgh, as well as continued opposition to lengthy periods of Conservative government, and anger at the imposition of Brexit against the wishes of a clear majority of Scottish voters.

The Queen in Edinburgh on the day in 2015 when she became the longest-reigning monarch in British history

The Queen in Edinburgh on the day in 2015 when she became the longest-reigning monarch in British history

"People in Scotland are now much more likely to say they feel wholly or primarily Scottish than was once the case," says Sir John.

However, he reckons most of the movement happened between the Queen's accession to the throne in 1952 and devolution in 1999.

There is evidence, he says, that the strengthening sense of Scottish identity has helped to drive a fall in royalist sentiment here.

Of course there is a distinction to be drawn between the monarchy and the monarch, between the institution and the incumbent.

"If people are criticising the monarchy you very rarely hear them criticising Elizabeth II," says Scotland's pre-eminent historian, Prof Sir Tom Devine of Edinburgh University.

"I think she's probably been the most significant and influential British monarch since the union of 1707."

The Queen and Prince Philip at Balmoral with Princess Anne, Prince Charles and a baby Prince Andrew in 1960

The Queen and Prince Philip at Balmoral with Princess Anne, Prince Charles and a baby Prince Andrew in 1960

As the daughter of a scion of an aristocratic family in Strathmore, the Bowes-Lyons, the Queen certainly has strong Scottish credentials. She can trace her ancestry to King Robert II and King James VI.

"One of her grandchildren, Princess Eugenie, is on record as saying that her grandmother is happiest in Balmoral," points out Sir Tom.

The 50,000 acre estate and castle on Royal Deeside has indeed been a sanctuary for the Queen, a place for hunting, dancing and picnics with family and guests.

She was here in the run up to the referendum on Scottish independence in 2014 when a poll suggested that the campaign to secede was on the brink of victory.

Outside Crathie Kirk, upon hearing a reference to the impending poll, the Queen is reported to have said: "Well, I hope people will think very carefully about the future."

Buckingham Palace denied the comment was an improper intervention by the supposedly apolitical Crown, a denial which has been somewhat undermined by the then prime minister David Cameron claiming that, in essence, he helped to engineer it.

David Cameron's comments were said to have provoked extreme displeasure inside the Palace

David Cameron's comments were said to have provoked extreme displeasure inside the Palace

"Just a raising of the eyebrow even, you know, a quarter of an inch we thought, you know, would make a difference," he told a BBC documentary in 2019.

"It was certainly well covered and although the words were very limited I think it did help to put a slightly different perception on things," he added.

Sir Tom Devine says he was "slightly surprised about it", but adds: "It didn't cross a red line. She never does."

Mr Cameron had previously been overheard saying that the Queen had "purred down the line" on being told that Scotland had rejected independence by 55% to 45%.

Both of his comments were said to have provoked extreme displeasure inside the Palace, but the 2014 referendum was not the first time that constitutional controversy had surrounded Elizabeth.

The previous occasion was a Silver Jubilee speech to MPs and peers in 1977, at a moment when the Labour government was considering devolution for Scotland and Wales.

Queen Elizabeth's address to parliament in May 1977

Queen Elizabeth's address to parliament in May 1977

"I number kings and queens of England and of Scotland, and princes of Wales, among my ancestors, and so I can readily understand these aspirations," said the Queen.

"But I cannot forget that I was crowned queen of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland."

At this a murmur, perhaps of approval, rippled through Westminster Hall and the Queen paused before adding: "Perhaps this jubilee is a time to remind ourselves of the benefits which union has conferred, at home and in our international dealings, on the inhabitants of all parts of this united kingdom."

"We say we don't know her opinion on things," says Prof Whitelock. Yet on this crucial topic "we already knew what she thought. It was captured in that 1977 speech.

"She's absolutely committed to the union."

In the end, of course, the Queen was front and centre when the Scottish Parliament was reconvened in 1999, nearly three centuries after it had been adjourned by the Act of Union.

"It is a moment rare in the life of any nation when we step across the threshold of a new constitutional age," she told the first members of the renewed Scottish Parliament.

The Queen with First Minister Donald Dewar at the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999

The Queen with First Minister Donald Dewar at the opening of the Scottish Parliament in 1999

The Queen used her speech to praise the Scottish people for their "grit, determination and humour," as well as their "forthrightness" and "strong sense of identity".

These qualities, she added, "reflect a Scotland which — if I may make a personal point — occupies such a special place in my own and my family's affections".

Are those affections returned?

With support for both independence and a republic considerably higher among younger Scottish voters than previous generations — and with Charles markedly less popular than his mother — the long-term challenges for the monarchy in Scotland are very likely to increase.

"I know that there are plans quite soon after his accession for Charles to go on a tour of all the nations, but also there's a sense that [the Palace] is going to watch and wait and see how he's received," says Prof Whitelock.

"That shows how potentially up in the air that relationship will be."

The same "forthrightness" and "strong sense of identity" which Elizabeth praised in 1999 may yet challenge the existence of the nation to which she has dedicated her long life and reign.