Liz Truss cabinet: who are the key players in PM’s top team?

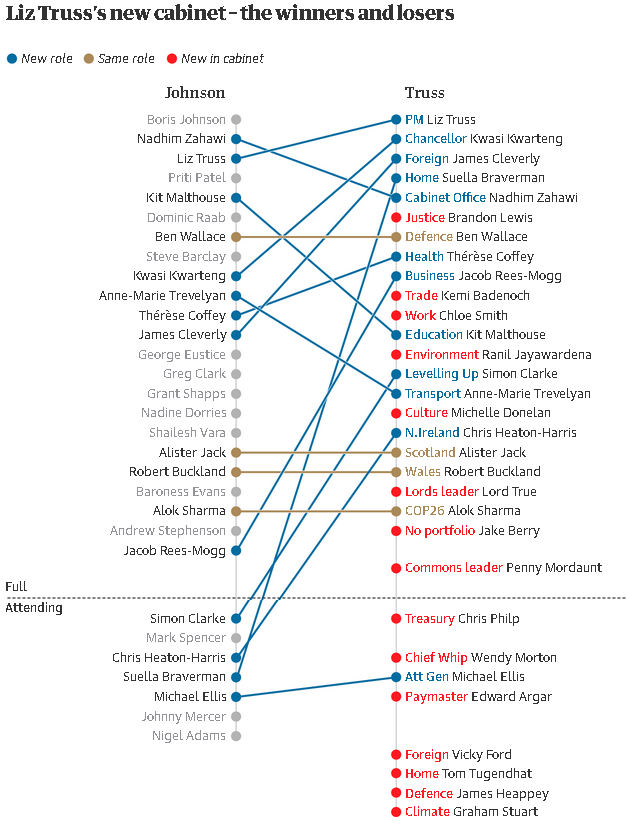

Liz Truss has started to assemble her government, with the top posts going to Kwasi Kwarteng (the chancellor), Suella Braverman (home secretary), James Cleverly (foreign secretary) and Thérèse Coffey (health). Here are some of the other members of the new cabinet.

Ben Wallace – defence

Ben Wallace

Ben Wallace

Managing to stay in the cabinet through the Boris Johnson-Truss transition and hold on to the job he clearly relishes is testament to the perception that Wallace has been an effective minister and to his judicious handling of the politics of succession.

When Johnson was ousted, many assumed Wallace would make his own bid to become the new leader. He did not, lying low and getting on with his day job, emerging in late July to endorse Truss – at which point her victory seemed assured.

Wallace, MP for Wyre and Preston North in Lancashire since 2010, undertook a series of junior frontbench posts before Johnson made the former Scots Guards officer his defence secretary when he took over at No 10 in 2019.

His profile was boosted during the chaotic evacuation of Kabul last summer, when his obvious irritation with the efforts of the holidaying foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, saw him portrayed, in contrast, as effective and diligent.

Brandon Lewis – justice secretary and lord chancellor

Brandon Lewis

Brandon Lewis

A fellow Norfolk MP with Truss – he has represented Great Yarmouth since 2010 – Lewis is a ministerial survivor, who has stayed on the frontbench since the David Cameron era, keeping his place with a mixe of hard work, an affable manner on the broadcast rounds, and notably loyalty.

Starting with a junior ministerial job in the then-communities department in 2012, Lewis has filled roles in the Home Office and Cabinet Office before being elevated by Johnson to become Northern Ireland secretary in 2020, despite representing an area about as far east from Belfast as you can get.

While he dutifully and energetically sought to patch up the Brexit-based repercussions of Northern Ireland policy, Lewis’s most eye-catching moment came when he openly told the Commons that the Johnson government’s plan unilaterally to amend the Brexit deal with the EU “does break international law in a very specific and limited way”.

This could be slightly awkward for the government’s new chief legal officer, who qualified as a barrister but spent most of his pre-Commons career in business.

Source: Institute for Government

Source: Institute for Government

Nadhim Zahawi – chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster, minister for intergovernmental relations and minister for equalities

Nadhim Zahawi

Nadhim Zahawi

Zahawi’s recent stint in the top rank of ministerial positions, first as education secretary and his recent few weeks as Johnson’s stand-in chancellor, largely come from his successful stint as health minister responsible for Covid vaccines.

Zahawi was credited with the success of the initial programme of jabs, which for a period brought Johnson a notable boost in the polls. He is a regular choice to go on radio and TV, where he has the ability to sound sensible while saying little.

An attempt to succeed Johnson went very poorly, resulting in Zahawi being eliminated in the first round of MPs’ voting and a slightly belated decision to endorse Truss, which was not enough to keep him at the top table.

The MP for the ultra-safe Conservative seat of Stratford-on-Avon since 2010, Zahawi was born in Baghdad to Kurdish parents who fled Iraq for the UK when he was nine. One of the Commons’ richest MPs, he was a co-founder of the pollsters YouGov, with interests in other areas such as petroleum before he became a minister.

Penny Mordaunt – Commons leader

Penny Mordaunt

Penny Mordaunt

The breakout star of the early days of the Tory leadership contest, where she came second in every round of MPs’ voting, apart from the crucial final one, Mordaunt may well have hoped for a more prominent role than Commons leader.

A relative veteran in modern Conservative circles – an MP since 2010 and on the frontbench for eight years – Mordaunt had long been talked about as a potential leader in waiting, and is popular with Tory members, but was pipped by Truss and now risks being a marginalised figure.

Mordaunt is a strong Brexiter who is socially liberal by modern Conservative standards, something that seemed to count against her in the leadership race. She has strong military ties and a resonant backstory, spending a period as a teenager helping to bring up her younger brother after their mother died.

On the frontbench she has had a varied career, with cabinet posts including international development and then defence secretaries, before moving to a junior trade role. Her boss there was Anne-Marie Trevelyan, who during the leadership race was withering about Mordaunt’s work ethic, which could make for some awkward moments at the cabinet table.

Jake Berry – minister without portfolio/party chair

Jake Berry

Jake Berry

The ministerial title simply means the Rossendale and Darwen MP can sit in the cabinet, as party chair in a non-governmental political role. Berry’s job will be to feed back the views of members and other MPs to Truss.

Berry chairs the Northern Research Group of Tory MPs, and was minister for the “northern powerhouse” under both Johnson and Theresa May. Under Truss he will be a key voice not only to the “red wall”, but also on wider levelling up issues, on which she appears notably more lukewarm than her predecessor.

In what is largely a cabinet of loyalists, Berry will have an important role for Truss if she wants to keep an already somewhat fractured parliamentary party behind her. As party chair he will hope to do better than Oliver Dowden, Johnson’s choice, who stepped down after humiliating byelection losses.

Alok Sharma – Cop26 president

Alok Sharma

Alok Sharma

One of few survivors in the same role in the cabinet – but principally because the job, in which Sharma oversaw the climate conference in Glasgow last November, will wind down when the next such annual event, Cop27, takes place in Egypt in November. His top-level future beyond then would seem uncertain.

Jacob Rees-Mogg – business, energy and industrial strategy

Jacob Rees-Mogg

Jacob Rees-Mogg

One of the most prominent – if not always most popular – ministers of recent years, Rees-Mogg is another Conservative whose longtime advocacy of lower taxes and a smaller state chimes with Truss’s beliefs.

He has been rewarded with a key portfolio, one taking in the climate crisis, to the dismay of green groups given his record on scepticism in this area.

While the 53-year-old Old Etonian feels like a long-term government fixture, he joined the frontbenches under Johnson only in 2019, becoming leader of the Commons, more recently taking on the extravagantly worded title of minister for Brexit opportunities and government efficiency, in the Cabinet Office.

When he first gained prominence, Rees-Mogg’s almost exaggeratedly mannered demeanour, robust views on Brexit and dry humour had some people tipping him as a possible future prime minister, the short-lived phenomenon known as “Moggmentum”.

Closer scrutiny, however, dented such ambitions, with Rees-Mogg criticised for a series of events including being pictured lying almost prone on a Commons bench as he listened to an opposition speech, and notably clumsy comments about the Grenfell Tower disaster.

Simon Clarke – communities and levelling up

Simon Clarke

Simon Clarke

From Truss’s slightly misfiring campaign launch to the media round the morning after she was confirmed as prime minister, the former chief secretary to the Treasury has been one of her most loyal and obvious – he is 6ft 7in tall – followers.

He, too, has been rewarded with a key ministry, and must implement what Truss has termed “levelling up in a Conservative way”, something many observers have taken to mean levelling up using much less state funding.

Part of the Conservatives’ 2017 intake, Clarke took the Middlesbrough South and East Cleveland seat from Labour, getting his first junior ministerial role, again at the Treasury, just two years later.

The affable former solicitor was regularly wheeled out under Johnson for morning ministerial broadcast rounds, managing to be ultra-loyal without coming across as overly slavish.

Clarke was a strong Johnson supporter, calling him “a superb PM”, but when the succession process began, he immediately backed Truss, and became a key member of her support team of MPs.

Kemi Badenoch – international trade

Kemi Badenoch

Kemi Badenoch

Badenoch was some way off victory in the 2022 leadership contest, but a lot of MPs believe the hugely energetic, fluent and ideologically certain former levelling up minister will be one of the key players the next time the Conservatives seek a new leader.

MP for Saffron Walden in Essex only since 2017, Badenoch has achieved some prominence beyond parliament largely through her energetic embrace of culture-war issues and her occasionally combative approach, including towards some journalists.

She had reportedly hoped to become education secretary, but Truss has instead given her a less public-facing role, where her approach could cause less controversy.

Opinions among MPs can be similarly mixed, but Badenoch’s advocates enthusiastically talk up her policy zeal, willingness to think on a grand scale, and ability to talk in a way that broadly resembles a normal human rather than a robotic minister.

Chloe Smith – work and pensions

Chloe Smith

Chloe Smith

Smith gets her first cabinet-level role – and one of the trickiest ones – but has been a fixture in the junior ranks of government, seemingly forever at the Commons dispatch box answering ministerial questions.

Yet another east of England MP in Truss’s cabinet, she has represented Norwich North since winning the seat from Labour in a 2009 byelection, aged just 27.

The former management consultant was on the frontbench within a year and has worked in five departments, including overseeing the controversial introduction of mandatory voter ID. Most recently she worked under Coffey at the Department for Work and Pensions.

In 2020 she was diagnosed with breast cancer, but announced last year that after treatment she was free of the disease.

Kit Malthouse – education

Kit Malthouse

Kit Malthouse

The fifth MP to hold this crucial post in just a year, Malthouse moves from being chancellor of the duchy of Lancaster in the interregnum after the mass departures of ministers under Johnson, where he was one of the few members of the government seeming to do any work over the summer.

A longtime ally of the former PM, Malthouse served as his deputy mayor for policing in London.

He was previously best known for lending his name to one of the attempts to repair relations over Brexit within the Conservative party – the Malthouse compromise. Like many of the solutions that MPs put forward, it proposed as-yet-unknown technology to avoid customs checks on the Irish border.

Under Johnson, Malthouse became minister for policing, tasked with the mass recruitment of officers to fulfil Johnson’s election pledge.

Ranil Jayawardena – environment, food and rural affairs

Ranil Jayawardena

Ranil Jayawardena

Moving to the cabinet from his former role as a trade minister, Tory MPs say Jayawardena will focus on reducing opposition within Whitehall to contentious trade deals that could threaten food and environmental standards.

His time in government has been relatively brief. Having worked under Truss at the Department for International Trade, he was one of her earliest supporters in the leadership contest. His only other spell on the payroll was as deputy chair of the Conservative party.

For seven years Jayawardena has represented North East Hampshire in the Commons. In 2017, he held the biggest majority in the country, by 27,772 votes.

After graduating from the London School of Economics, Jayawardena became a councillor, and worked for Lloyds Banking Group. He is a freeman of the City of London.

Anne-Marie Trevelyan – transport

Anne-Marie Trevelyan

Anne-Marie Trevelyan

Another ministerial do-anything, Trevelyan has taken up the often tricky transport brief after several other people reportedly turned it down.

A vehement Brexiter and particularly close ally of Johnson, who made her international trade secretary, Trevelyan has successfully made the transition to Truss’s administration despite initially backing Tom Tugendhat for leader.

After Tugendhat was eliminated she transferred her loyalty to Truss and helped her campaign, with a brutal attack on the rival candidate Mordaunt – who had been one of her junior ministers.

The MP for Berwick-upon-Tweed since 2015, the former accountant made it to the frontbenches under Johnson with a junior defence role, then into the cabinet in just two more years.

Michelle Donelan – culture, media and sport

Michelle Donelan

Michelle Donelan

In future years, Donelan’s fate seems likely to be the answer to the pub quiz question about the education secretary who lasted just two days in the job. She resigned 48 hours after taking the role as MPs tried to force Johnson to step down.

In fairness to Donelan, she had by then spent three years in more junior education roles, most recently as universities minister.

Donelan steps into the often controversial culture brief in place of Nadine Dorries, who is expected to be heading to the Lords, and Truss will hope for a slightly more sober handling of issues including the planned sale of Channel 4 and the online safety bill.

However, Donelan, MP for Chippenham in Wiltshire since 2015, is not herself averse to a culture war, having previously clashed with universities over what they saw as her prescriptive approach to free speech issues.

Chris Heaton-Harris – Northern Ireland

Chris Heaton-Harris

Chris Heaton-Harris

The modern Conservative party’s Mr Adaptable, Heaton-Harris has been given eight different ministerial posts since 2016, covering six different departments, and his second in the cabinet.

In keeping with this role, the former chief whip’s emergence as Northern Ireland secretary follows an apparent uncertainty within Team Truss as to who to appoint to the job, one of the few cabinet roles not nailed down for several days.

The MP for Daventry since 2010, Heaton-Harris is a former MEP who has held also jobs under May and Johnson, resigning from his Brexit department role under May in protest at her policy approach towards leaving the EU.

Despite his mild demeanour, Heaton-Harris can be notably ideological, as shown in 2017 when he faced accusations of McCarthyism after writing to vice-chancellors demanding a list of tutors lecturing on Brexit.

Wendy Morton – chief whip (attends cabinet)

Wendy Morton

Wendy Morton

Very much an unknown with the public – possibly even to a few of her fellow MPs – Morton has represented the West Midlands constituency of Aldridge-Brownhills since 2015, and has held a series of ministerial roles since 2018, starting as a junior whip under May.

Unlike many of her May-period colleagues, Morton survived into the Johnson era, moving into junior roles in the Ministry of Justice, Foreign Office and Department for Transport, in the latter role taking on the tricky remit of rail travel, among other areas.

Educated at a comprehensive school in North Yorkshire and the Open University, Morton as a diplomat and worked in sales and marketing before entering parliament – trying initially to be selected to the Richmond, Yorkshire constituency now occupied by Rishi Sunak.

Michael Ellis – attorney general (attends cabinet)

Michael Ellis

Michael Ellis

In recent months as part of his previous wide-ranging job in the Cabinet Office, Ellis was most visible to parliamentary observers as the man wheeled out to defend Johnson over almost anything in awkward Commons debates.

As an experienced barrister before entering parliament in 2010, Ellis was very capable of maintaining a straight-faced professional demeanour while batting away questions over everything from Downing Street parties to Chris Pincher and the supposedly secure position of the prime minister.

The MP for Northampton North, Ellis has held a series of ministerial roles since 2016, including an earlier stint as attorney general under Johnson.

Alister Jack – Scotland

Alister Jack

Alister Jack

Another rare cabinet survivor, the Dumfries and Galloway MP has held the role ever since Johnson became prime minister, only two years after he was first elected to the Commons in 2017.

A successful businessman before becoming an MP, Jack did not join the exodus of ministers in the last days of Johnson, to whom he stayed loyal, and was neutral during the race to succeed him.

Robert Buckland – Wales

Robert Buckland

Robert Buckland

Buckland is another continuation from Johnson – although he only took on the job in July amid the churn of ministers as Tory MPs sought to depose the then-PM.

The former justice secretary may have hoped for bigger reward after attracting the ire of a number of fellow MPs for very publicly switching his support from Sunak to Truss last month, as it became obvious she would win.

Nicholas True – Lords leader

Nicholas True

Nicholas True

A veteran Conservative operator, who entered the Lords in 1993 after a series of jobs in the Tory party and for ministers, including in John Major’s No 10, True replaces Natalie Evans, who had survived in the role through both the May and Johnson eras.

True must try to rally Tory peers to push through legislation that other parties could try to block, especially should it bear little resemblance to the party’s 2019 election manifesto.