How much more does a pint cost in London? How inflation is affecting different parts of the UK

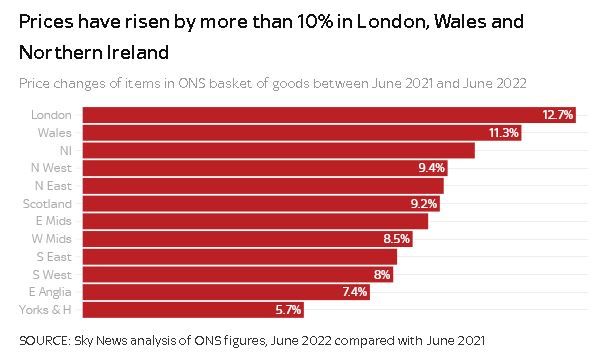

Across the country in June, inflation is at its highest rate in 40 years, but Sky News analysis of the latest ONS figures shows that shoppers in London are facing price rises that double those seen in Yorkshire.

As well as London, prices in Wales and Northern Ireland have risen by more than 10% compared with last June, higher than the headline national inflation figure of 9.4%.

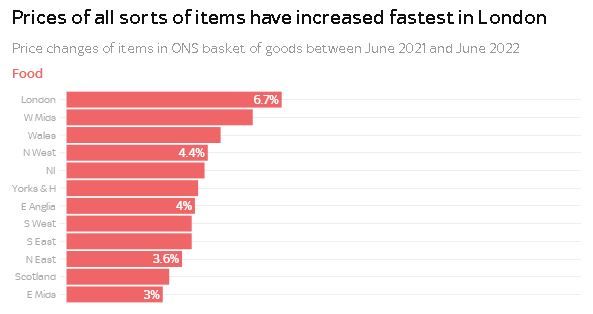

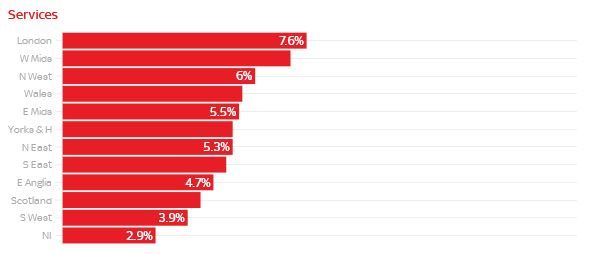

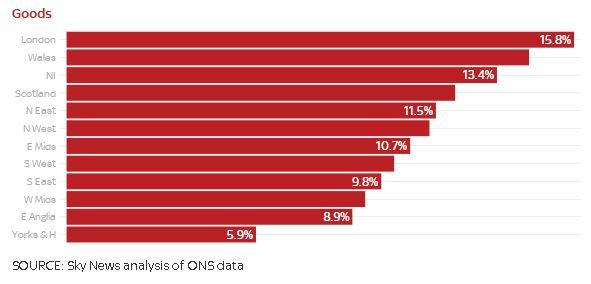

Food prices have increased by less than services overall, and both significantly less than goods, but there is still a clear divide in how prices of different types of items are rising in different nations and regions of the UK.

The ONS measures inflation by keeping a record of the prices of 730 foods, goods and services that are intended to be representative of what British consumers spend their money on. The list, known as "the shopping basket", is updated every year so it remains relevant.

Part of the way they keep track of price changes is by visiting stores around the UK and recording prices seen on the shelves, which are then published in full, including a weighting based on the type of shop and how representative the item is. For example the price of a major brand seen in lots of shops might be given more weight than an own-brand version of the same item.

The figures that we have analysed only cover items found in store, while the ONS also records a proportion of prices online and over the phone.

Significant costs like petrol, energy and housing are also excluded from the release, so figures are not directly comparable to the headline ONS inflation figure. They do however give an insight to the different cost-of-living experiences that people face in different parts of the UK.

'Personal spending habits really matter'

It does not necessarily mean that people in places where prices have risen fastest will end up worse off.

Jack Leslie, a senior economist at the Resolution Foundation, who specialises in inflation and wealth inequality, said that "personal and local spending patterns really matter."

"If you're someone who lives in a small, energy-efficient flat in London who doesn't own a car, your personal inflation level is going to be hugely lower than someone who is living in a leaky mansion in the highlands of Scotland, because the energy price cap has gone up and you have to drive loads.

"There has been a longer-term trend that housing and other living costs have increased in areas where wages are highest, so there are smaller living standards gaps between nations and regions than might appear on the surface. These figures feed in to that.

"But it's not a good news story that these gaps are closing, it's just that some places are doing worse than others. Everywhere is going to be hit really hard by the cost of living crisis. No one can escape it. Peoples' real incomes are falling and that is causing a lot of stress and difficulty and potentially pushing people into poverty."

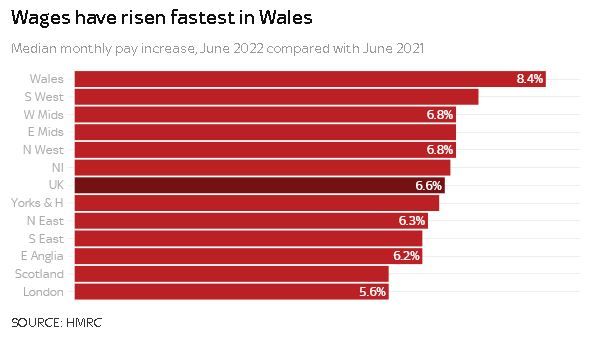

Figures released by HMRC on Tuesday show that while average wages have risen across the UK, prices have risen faster on the whole.

People still earn more in London than other parts of the country, £2,556 per month compared with a UK average of £2,108 and less than £2,000 across the north of England, the midlands, the southwest and Northern Ireland.

But lower wage growth and higher living costs mean that there is not the same gap when it comes to living standards.

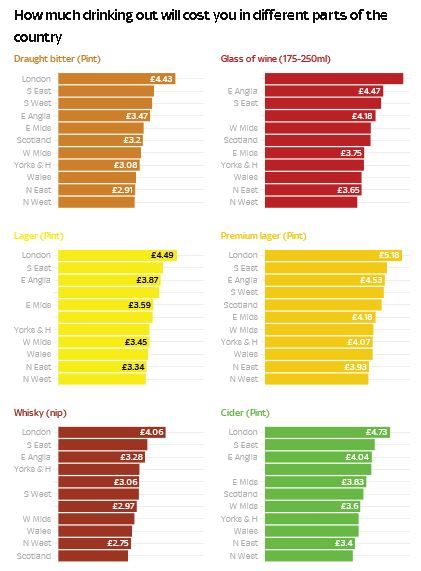

How much more is a pint in different parts of the country?

Our analysis also shows the range of prices of certain items in different nations and regions.

While there is only a five pence difference between the average price of milk in the cheapest part of the country compared with the most expensive (£1.28 for four pints of whole milk in the northwest vs £1.33 in the northeast), there are starker differences when it comes to things like alcohol.

A pint of draught bitter will set you back £2.89 in the northwest, on average, but £1.50 more in London. It's a similar story for wine and lager, while the cheapest whisky - perhaps unsurprisingly - is in Scotland.

Mr Leslie says that regional differences in hospitality costs usually reflect wage differences: "A big chunk of the cost of eating out would come from the cost of employing the chef, the waiters and whoever else works there."

Other factors that make a difference to price changes at a local level include the amount of produce that is imported vs that which is made or grown locally, and the types of shops people are used to using.

Mr Leslie says that during the pandemic "people became less willing to go to the big supermarket, and there was more demand for local corner shops", particularly in built-up areas.

He added: "I would expect imported products to have risen in price faster than non-imported, because of disruption to supply chains and exchange rates."