Boris Johnson sighed in relief – then the message from UK local elections took hold

n Friday morning, as broadcasters, pollsters and political analysts tried to make sense of a mixed bag of early results from the previous day’s local elections, no one was quite clear who had performed the best. All the party leaders seemed happy enough and the political messages were blurred.

Boris Johnson was said by people in Downing Street to be in a buoyant mood when he sat down at his desk at 8.15am, believing the heat was off him. He had told a meeting with his advisers the previous day that “we are going to get our arses kicked”. But while he could see his party had indeed taken a beating and was losing seats, it seemed that a Tory meltdown had been avoided, and that Labour was failing to win back support behind the red wall.

Keir Starmer was also cheery, outwardly at least, as he arrived in Barnet on Friday, hailing his party’s conquest of the Conservatives in that London borough, and even more impressively in Westminster and Wandsworth, as “a turning point” for Labour.

Starmer was, however, glossing over rather less good news outside the capital, as an early narrative was slowly developing that Labour had flopped. Meanwhile Liberal Democrat leader Ed Davey was declaring the elections no less than “historic” for his party as it clocked up some decent gains across the country.

Twenty-four hours later, however, after the full national picture emerged, and results from Scotland and Northern Ireland – both of which have raised profound constitutional questions about the future of the UK – there was an altogether different sense about Thursday’s elections.

The Tories had in fact done far worse than it had seemed earlier, particularly in the south of England, and had shed more than 400 seats, while Labour had performed much better and had gained more than 250. “Shocking,” said one minister, adding that Johnson would not recognise that he had caused the problem. “[The PM] won’t care though. We’ll have to lose a general election first.”

This weekend, some Conservative MPs in traditional Tory areas in the south are so angry and worried by the southern revolt among their grassroots supporters that they are again considering whether to oust him.

On Monday, London Tory MPs will meet to discuss what to do. One said: “We had thought that our people would stay at home and not vote. That is what we were told. But they didn’t. They came out in anger to kill us.”

Keir Starmer speaks to supporters in Barnet, north London, after Labour took control of the council.

Keir Starmer speaks to supporters in Barnet, north London, after Labour took control of the council.

Another said: “There is a feeling among our voters that we have forgotten London and them, that all we care about is the red wall.”

Other Tory MPs were less sure, saying they feared a failed coup could leave them in a worse position. “He is so unpredictable – we want a clean kill and a clear alternative,” said one senior Tory and Johnson critic. “Johnson is the problem.”

The central challenge for the PM of holding together his 2019 coalition of red wall voters and traditional Tories has been exposed in these elections as a potentially fatal problem.

To add to Johnson’s woes – and part and parcel of them – is a revival of the Liberal Democrats, which gained pace on Thursday and is also unnerving his backbenchers. The Lib Dems took councils in Conservative areas, including Somerset county council and Woking borough council, as they continued to fight back in the south-west and other rural areas where they were strong before joining the coalition in 2010.

Speaking to the Observer, Davey described the results as “a tidal wave” that had defied his best expectations and led him to re-examine and expand the party’s general election ambitions. “We’ve spoken about the blue wall, but we’ve expanded that into the west country and rural communities. It’s more serious than it was when we won the Chesham and Amersham byelection last year … our battleground with them is beginning to expand.

“We are going for the Conservatives. We think they are absolutely ruining our country.”

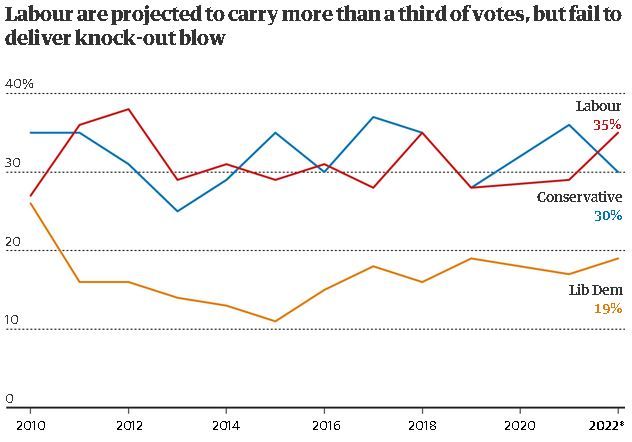

Data emerged later on Friday confirming the Lib Dem surge and suggesting that Starmer could indeed lead the next government. The BBC projection for the national vote share put Labour on 35%, the Tories on 30% and the Liberal Democrats on 19%.

Labour also performed well in Scotland, pushing the Tories into third place and suggesting all is not lost for Starmer’s party north of the border. “That was a big mood-changer for us,” said a member of the shadow cabinet, “when we saw what was happening north of the border.” The number of councillors elected in Scotland rose for every party except the Scottish Conservatives, who dropped 63. After 15 years in power, the SNP increased its tally by 22, with Labour gaining 20, the Lib Dems 20 and the Greens 16.

Candidates and other party representatives wait as ballot papers are counted in elections for Sunderland city council.

Candidates and other party representatives wait as ballot papers are counted in elections for Sunderland city council.

With Sinn Féin on course for a stunning win in elections to the Northern Ireland assembly, Scotland’s first minister Nicola Sturgeon was not slow to point out that the elections – which also saw a strong performance for Plaid Cymru in Wales – had raised “big questions” about the very future of the UK “as a political entity”.

“If [Sinn Féin] emerge as the largest party today in Northern Ireland, which looks very likely, that will be an extraordinary result, and something that seemed impossible not that long ago,” Sturgeon said.

“There’s no doubt there are big fundamental questions being asked of the UK as a political entity right now. They’re being asked here in Scotland, they’re being asked in Northern Ireland, they’re being asked in Wales, and I think we’re going to see some fundamental changes to UK governance in the years to come. I am certain one of those changes is going to be Scottish independence.”

The ultimate goal of Sinn Féin – whose leader in Northern Ireland, Michelle O’Neill, declared the election to be a “historic day” – is for Northern Ireland to leave the UK and become one country with the Republic of Ireland.

The Northern Ireland Act 1998 – which followed the signing of the Good Friday peace agreement – states that the UK “shall not cease to be so without the consent of a majority of the people of Northern Ireland voting in a poll”. It also says that the Northern Ireland secretary of the day will agree to hold a poll if it appears “likely” that a majority of people want a united Ireland.

While opinion polls suggest that is not likely in the short term, party leader Mary Lou McDonald said on Friday that planning for a unity referendum would come within a “five-year framework”.

Some Conservatives blame Johnson and Brexit for putting strains on the UK. One senior figure suggested MPs should act before it was too late. “It is really bad, they are fucking the Union by keeping him.”

This week, the PM will be hoping that the Queen’s speech will reassure both his own MPs and party members, as well as the country, that he is the right person to lead the nation. It will focus on measures to “grow the economy” and help people with cost-of-living pressures such as the price of energy, and will include bills to take what he sees as the “opportunities of Brexit”, including deregulation.

But rather than strengthening his position as he believed at first, Thursday’s elections may well have destabilised Johnson further, by bringing into the open many of the huge problems – Brexit-related and not – that his government is responsible for.

Labour’s progress on Thursday has been overshadowed by its own problems over lockdown gatherings, with Starmer now being investigated by Durham police for drinking a beer in an MP’s office last year. But Johnson’s premiership remains in great peril as civil servant Sue Gray prepares to publish her report on Partygate, and the Metropolitan police complete their investigation.

Ominously for Johnson and the Tories, there are more electoral tests soon. The Lib Dems have already started campaigning in Tiverton and Honiton, where a byelection will be held next month after the resignation of Tory MP Neil Parish, who admitted looking at porn in parliament.

The constituency includes the prosperous Devon town of Cullompton, normally safe Conservative territory. There, lifelong Conservative voter Tim Cox said he was considering voting for a different party for the first time. “It’s just the general behaviour of the Conservative party. It’s pretty shocking – it’s appalling,” he said, pausing on the high street. “Johnson lied. It’s the bare-faced lies he’s told. It’s all about personal character to me, whether you are believable or credible as a leader of the country. There are a few of them in the cabinet, including Johnson, who just aren’t.”

There seems to be some desire for change in the constituency, which has been staunchly Conservative since its creation in 1997. Ryan Lacey-Mills, 34, who works in car sales, voted for Johnson in 2019 but now felt the PM was a spent force. He is also weighing up the offer from other parties. “[Johnson] has had his time. He did Brexit,” he said. “Whether it is his fault or not, something needs a shakeup. It’s time for a change.”

Even those still planning to vote Conservative struggle to summon up much enthusiasm. Steven Morris, 69, believes Johnson will have to go eventually. He can’t forgive the parties that took place in No 10 when the country was in lockdown. “I’ve got asthma. I was actually locked up for two months when it all kicked off – and to think they were having parties really upsets me,” he says, cradling a wrapped portion of fish and chips. “I always thought the Conservatives had got standards, but Boris hasn’t got any.”

As they eye Tiverton and Honiton, the Lib Dems have their blood up. Johnson may be able to soldier on after Thursday’s local elections but whether he could survive a byelection defeat in a safe seat in a few weeks time is another matter entirely.